– tl;dr –

To communicate well, apply techniques of error-correcting conversations, especially whenever someone says something that sounds dumb, or otherwise doesn’t make sense:

Make sure you’ve heard their words correctly. “Did you just say <the words you heard>?”

Use your understanding to create a prediction for an implication outside the immediate bounds of what they’ve said, and see if their understanding agrees with your prediction. “Does that mean that we would also expect X/Y/Z?”

Rinse and Repeat.

Management is about developing comparative advantages, both within yourself, and among your teams. The goal for yourself is to minimize context switching costs on a daily basis. The goal for your teams is to ensure that no matter what surprise tomorrow brings, your team has a spread of comparative advantages that will let it tackle the work with efficiency and effectiveness.

As an addendum, when hiring, forget the adage about “T-shaped people”. Instead, seek out and hire Koosh ball people: people with multiple, separate areas of deep skill. This maximizes the chance of your team members having really distinct and applicable comparative advantages, no matter the challenges ahead.

Leaders have two jobs: to cultivate pervasive trust, and to delegate well.

There’s a lot said about culture, and most of it is BS. The only thing that matters in a startup’s culture is whether or not all members of the company share a deep trust with each other. The operative question is “Would they take a bullet for me?”. When asked from anyone’s perspective, and directed at anyone else, the answer had better be “yes”. As a leader, judge every action, policy, incentive, and plan with regards to whether it deepens or depletes trust.

Delegation is a two-way contract. It must have a clear vision and strategy defined from above, and tactical authority and true acceptance from below. The delegator specifies the goal and the delegatee specifies what they need to accomplish it. Vitally, the delegatee must truly be able to say no if they deem the task impossible given the resource constraints.

Startups are hard. These are my guidelines for making them a little bit easier.

These thoughts are, of course, applicable to many other situations in life as well, but by using the word “startup”, I hope to attract the attention of people in startups, for whom this advice may make a tangible difference between success and failure.

This is the most directly actionable advice I have, distilled from more than a decade in the field, and I wish someone had presented it to me, in just this way, when I was new.

Communication

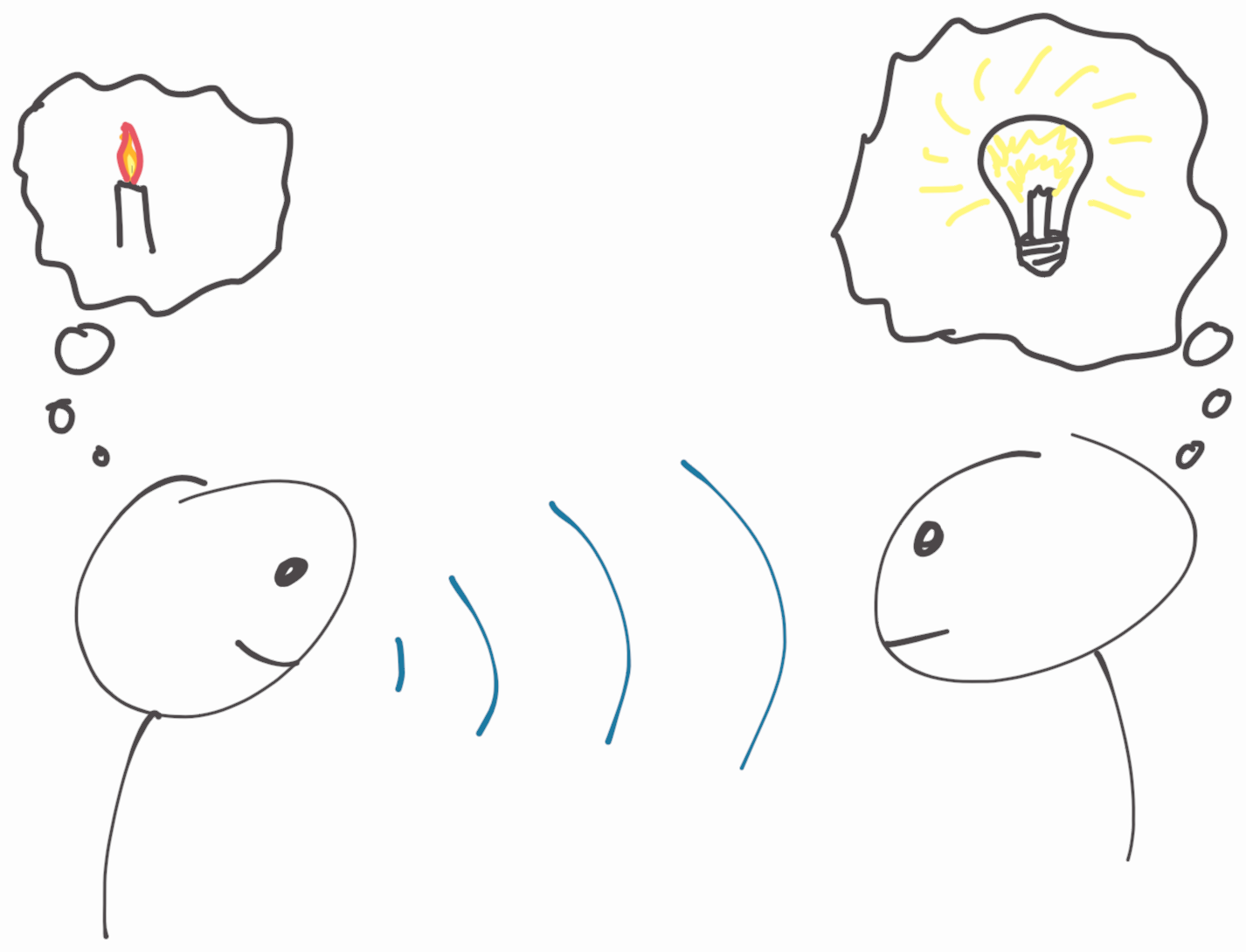

The typical communication involves three distinct translation steps.

First, an idea in one person’s mind must be translated into words that are spoken.

Second, the spoken words are translated into heard words.

And third, the heard words are translated into an idea in the second person’s mind. Each of these translation steps is an opportunity for errors to creep in, and miscommunication to result.

this happens to everyone

this happens to everyone

This is the origin of a peculiar paradox: everyone has heard plenty of other people say dumb things, yet when asked, everyone will tell you that they try very hard not to say dumb things themselves!

The solution is that most of the time when something sounds dumb, it’s because the idea that you’ve ended up with in your mind (after three steps of potential translation error) doesn’t match the idea that was in the speaker’s mind. Thus, they may have been trying to express an idea that made perfect sense to them, but by the time it’s reached you it just seems sort of stupid… because it’s not the same idea.

Most of the time you can resolve these sorts of issues by borrowing a page from the scientific method.

Step 1: Clean your data. Make sure you’ve heard them correctly by just repeating their words back to them and asking if that’s what they’ve said.

Step 2: Come up with a prediction about an implication of the idea that’s outside the direct bounds of what they’ve just said, and see if they agree with your prediction.

Step 2 is usually the tricky one. The idea here is that since there’s no way to directly compare the neural pulses in your brain with those in theirs, the best you can do is try to make sure that all of the predictions that arise from the idea in your mind match all of the predictions of the idea in their mind. If this is broadly true, then for all practical intents and purposes, the two ideas are the same.

Here are some examples of what this might look like:

Person A: “Unemployment is bad.”

Person B: “Do you mean that no one should be allowed to quit their job and take time off?”

Person A: “No! Just that if too many people want jobs and can’t find them, it’s not good.”

– or –

Person A: “Facts aren’t always true.”

Person B: “What? Like linear differential equations don’t have unique solutions?”

Person A: “Naw, just that when someone shows up with some data, you have to question it! How was it collected? Is there a bias towards one viewpoint above others? Which industry group paid for it?”

– or even –

Person A: “This surface needs to be smooth.”

Person B: “So you mean you want it to be polished so it doesn’t feel rough?”

Person A: “More than that! We have to make sure that reflections on any part don’t have sudden changes!”

Management

Management is about developing and ensuring comparative advantages, so that tasks can get done as efficiently and effectively as possible.

If you’d like a refresher on comparative advantages and why they’re important, check out the beginning of my essay on Comparative Advantage and the Theory of Intertemporal Self-Trade.

For managing yourself, you can create comparative advantages between different days by trying to arrange your schedule to minimize context-switching costs. This is related to Paul Graham’s idea of the Maker Schedule vs Manager Schedule, but slightly more expansive.

Of course, a la PG, it’s better to schedule meetings together in a concentrated batch, and ideally to keep them fully separate from blocks of time dedicated to deep work. But we can go further than this and say that even among blocks of deep work, it’s usually more efficient to focus on just one thing at a time, for as long as possible; so if you’ve got a to-do list that consists of a database migration, refining a new SVM model, and setting up A/B tests for marketing copy, for the love of god, do them one at a time if at all possible.

Managing teams is a little different. The focus becomes learning the distinct comparative advantages of your team and ensuring that your team members are free to dedicate themselves to work that aligns closely with their comparative advantages. Most teams get this right to first order—have the database experts work on the database, and the UI designers focus on the frontend—but in the case of startups, first order correctness doesn’t help much when you’re working with fewer engineers than you’d like, most of them generalists, and you certainly don’t have entire departments dedicated to specific functions.

In those cases you’ve got two options, and you should pursue them both simultaneously.

On one hand, get to know your team members. Watch their performance on various tasks closely and build up a good mental model—as accurate as you can!—of their comparative advantages. Figure out who’s the fastest for exploratory work, and who’s the most thorough for vital functions. Determine who can hold their own in open presentations, and who prefers communication through written documentation. And do your damndest to make sure that every one of your team members gets to focus on their comparative advantages.

On the other hand, be open with your team members and talk to them, often, about where they see their current comparative advantages, and what new ones they’d like to develop—they might surprise you! And of course, it’s vital to not only encourage your team members to develop new or deeper comparative advantages, you must make doing so part of their job. This means that continuing education can not be optional; time must be formally and officially set aside for it.

Continuing education can be tricky to mandate. Too often, it turns into useless corporate classes and gets viewed as a chore. Instead, it’s best to leave the direction and method of the learning completely up to the individual doing the learning. If they want to audit a class online, then they get to audit a class! If they want to study a book, then they get to study a book! And if their chosen topics don’t align directly with the work they’re currently doing, so much the better: it just means that when new, unexpected challenges come down the line tomorrow, you’re more likely to have someone able to tackle them.

To judge their efforts, simply suggest some sort of presentation on the learnings at the end. This can be as elaborate as showing off a small project to other teammates, or as simple as a verbal discussion with you (their manager) or another colleague. The important part is to ensure interaction with an outside voice that can ask questions, for that is when some of the most valuable learning takes place. Study groups, in particular, are excellent at this.

A note on hiring…

The goal in hiring is to bring in new team members who have sets of comparative advantages that serve as good complements to those possessed by your current team members. The problem is that while you may know what tasks need doing today—and so you can interview for them—you will not generally know what tasks need doing tomorrow.

The solution is to try to pick candidates who have significant additional comparative advantages outside of the set that you directly need for your current tasks. Koosh ball people instead of T-shaped people.

The way I do this is to ask candidates in interviews to “teach me something technical”. I tell them to pick a topic they’re very comfortable with, and then as they teach me about it, I will ask questions about related ideas or corner cases that hopefully they haven’t encountered directly before. I even tell them exactly what I’m looking for: not particularly correct answers (because I’m not likely to be a good judge of correctness on a topic I’m probably unfamiliar with), but instead that I’m looking to understand their thought process and approach when I throw them a curveball.

Once they pick a topic and dive in, I let them talk for maybe fifteen minutes or so, asking only clarifying questions at first, so that I understand what they’re telling me. Then I take a moment and come up with my curveball. This is almost always just asking them to reconsider the topic with some change to one of their fundamental assumptions: either a difference in constraint, a difference in the scale of some number, or similar.

For example, here are some descriptions of actual interviews:

Candidate A told me about their time working on nuclear power plants, and described in detail the challenges associated with the cooling systems. I asked them “Imagine that word of your expertise gets around, and tomorrow NASA shows up at your door, wanting a nuclear reactor for a new space station. How does your cooling system change without gravity?”.

Candidate B told me about a mesh sensor network that they put together for their garden. I asked them “How would you tackle this if your garden was huge and you still wanted to instrument every plant? What if it wasn’t just a garden, but a full scale farm?”

The point is not what solution they give to the curveball question, but how carefully they think through it. A bad answer will be simple: “Oh, I would just change X and that would be it”. A great answer will show them progressing down, discovering and resolving issues as they consider the ripple effects of your modified assumption: “Well, the biggest effect from that change would be X, which we could try solving by adjusting Y, but then that brings up the question of Z…”.

There is no topic that can survive a change in scale of multiple orders of magnitude, or the switching of a basic assumption, without triggering a fractal cascade of effects. The only metric is how far down that chain they can go.

The reason I do this is to learn how deeply the candidate digs into topics that they’re faced with. If the answer is “very deeply indeed”, then you can be pretty confident that they probably bring this behavior to lots of topics, and so they’re almost certain to have plenty of deep comparative advantages to bring to the table outside their direct job description.

In a startup, you need these people. They’re the only way to get ahead of the curve and give your team the best chance possible of having suitable comparative advantages already in place when unexpected challenges show up¹.

Leadership

The only thing that matters in a company’s culture is deep, mutual trust between all of the team members at the company, and as a leader, you are responsible for cultivating that trust.

This is important, so I’ll say it again.

No one actually cares if you have ping pong tables, dogs in the office, weekly happy hours and board game nights, or even an on-site masseuse. Those are all bullshit and meaningless towards the success of your startup if you don’t have deep, mutual trust. Similarly, if you do have deep, mutual trust, you can be working out of an unfurnished basement for all anyone cares, and still have full engagement from your team and produce amazing results.

The metric for this trust is the question “Would they take a bullet for me?”. This doesn’t need to be literal, but the gist is that anyone in your company, thinking of anyone else in the company that they interact with, should feel assured that the other person would be willing to take risk, flak, or trouble onto themselves for the sake of the questioner.

This means managers taking the heat when one of their team screws up. It means colleagues giving credit to otherwise invisible advice from others when it helps their project succeed. And it means the CEO rolling up their sleeves and turning a god damned wrench if it’s truly “all hands on deck”.

As a leader, you need to evaluate everything around you for whether it encourages or diminishes this kind of trust. Get it right and prosper with engaged colleagues, good retention, and full buy-in to the mission. Get it wrong and suffer.

For example, if you want to make sure that your remote employees feel like a full part of the team, don’t bring them into HQ for a bonding offsite, but send your HQ team on an offsite to the remote location.

Another: don’t expect your team leads to take flak for their reports if the VPs don’t take flak for their team leads in turn. And make this metric a part of their performance reviews!

Jeszcze raz². If the CEO is leaving the office while other team members are still crunching, then the CEO had better offer to get them coffee on the way out.

Delegating well

Too many people think that delegation is simply the act of telling someone else what to do. This is a recipe for disaster, missed deadlines, and a breakdown of trust.

Instead, delegation must be a two-way contract.

The delegator is charged with maintaining a comparative advantage in understanding the bigger picture, and specifying the desired goal.

The delegatee should have a comparative advantage (and freedom of choice!) in the tactical implementation required to achieve the specified goal, and crucially, must be responsible for specifying the needed resources (people/time/material)³.

Finally, the delegator and delegatee must reach an agreement as to the final nature of the goal, and resources available to reach it. This must be a real agreement. That means that the delegatee must be able to say no.

Without the ability to say “no”, it is far too easy to default into an endless stream of under-resourced death marches, chasing impossible goals and achieving little besides record burnout and employee churn.

Do note that the ability to say “no” doesn’t mean that you have to arrive at “yes” on the first pass. It’s completely reasonable to take a couple rounds of back-and-forth between the delegator and delegatee, carefully refining the precise definition of the goal, and likewise the precise resources needed to achieve it. This is an incredibly valuable process⁴.

Delegation and trust are tied together. Proper delegation enhances trust. Poor delegation destroys it.

One final note: much of this last section on leadership is distilled from the insight of two sources: Robert Coram’s biography of John Boyd and Chet Richards’s book on applying the strategy of John Boyd to business. Both are excellent reads.

-

Or, as we call it in startups, “on Tuesday”.

-

“Jeszcze raz” – roughly “once again” in Polish.

-

This is the only time I will come close to referring to “people” as “resources”. I hate it when this is done, and only do it here because I’m using “resources” to mean a broader set, including also time, equipment, tooling, money, etc. If you use the word “resources” when all you really mean is “people”, then then only thing you’re doing is obfuscating and anonymizing the fact that you’re referring to human beings, and there is surely a special place in hell for you… right next to people who talk at the theater.

-

Also known as “planning”.