– tl;dr –

As a guiding principle, ask yourself “What, in these life circumstances, do I have a comparative advantage in doing? For which of these things do I suspect this comparative advantage might only be temporary?”. Pick, for your focus, only things in which you enjoy a comparative advantage, with special consideration to those things where such an advantage might be fleeting.

In this way you can build up over your life a portfolio of skills, experiences, and accomplishments, and since each of these is rooted in a time of comparative advantage, this portfolio, summed up over your lifetime, will be beyond the production possibility frontier of what you could have managed had you chosen to pursue all things in moderation at all times, regardless of advantage.

You are, in essence, conducting trade between your past, present, and future selves.

“You there! Me in the future! I’ll work on those things I’m best able to make progress in now, and ignore those that you’ll be better positioned to develop later.”

Comparative advantage: what is it?

Comparative advantage is a beautiful concept from economics, and it’s probably the most important supporting pillar for the “trade is good” hypothesis.

We say that an entity has a comparative advantage in the production of some thing if that entity has a lower relative marginal cost associated with its production of that thing, vs the same measure for other entities.

Sounds abstruse, right? Let’s dig in…

Let’s start with an original example from the 1817 book that introduced the idea of comparative advantatge to the world in a formal way.

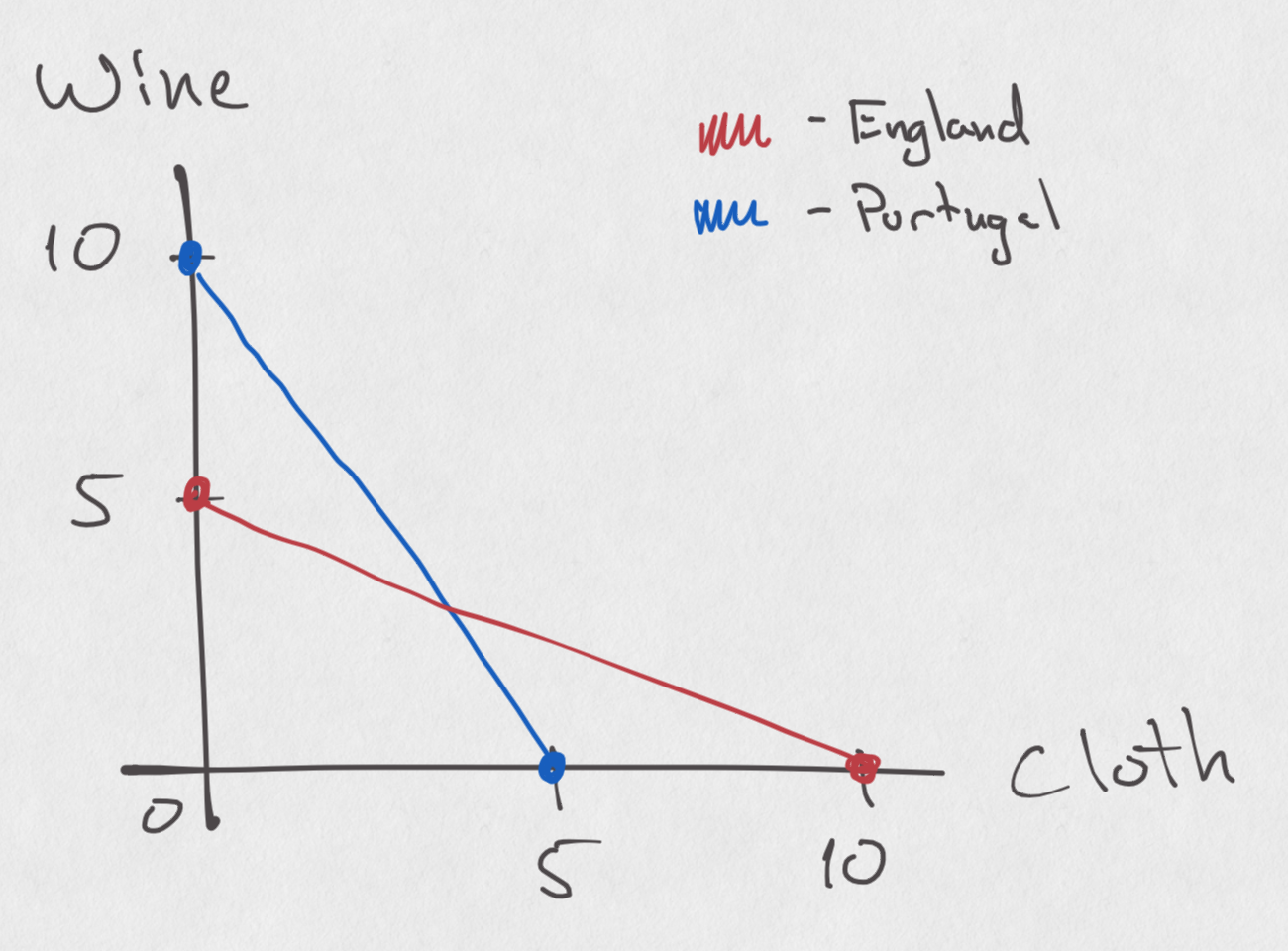

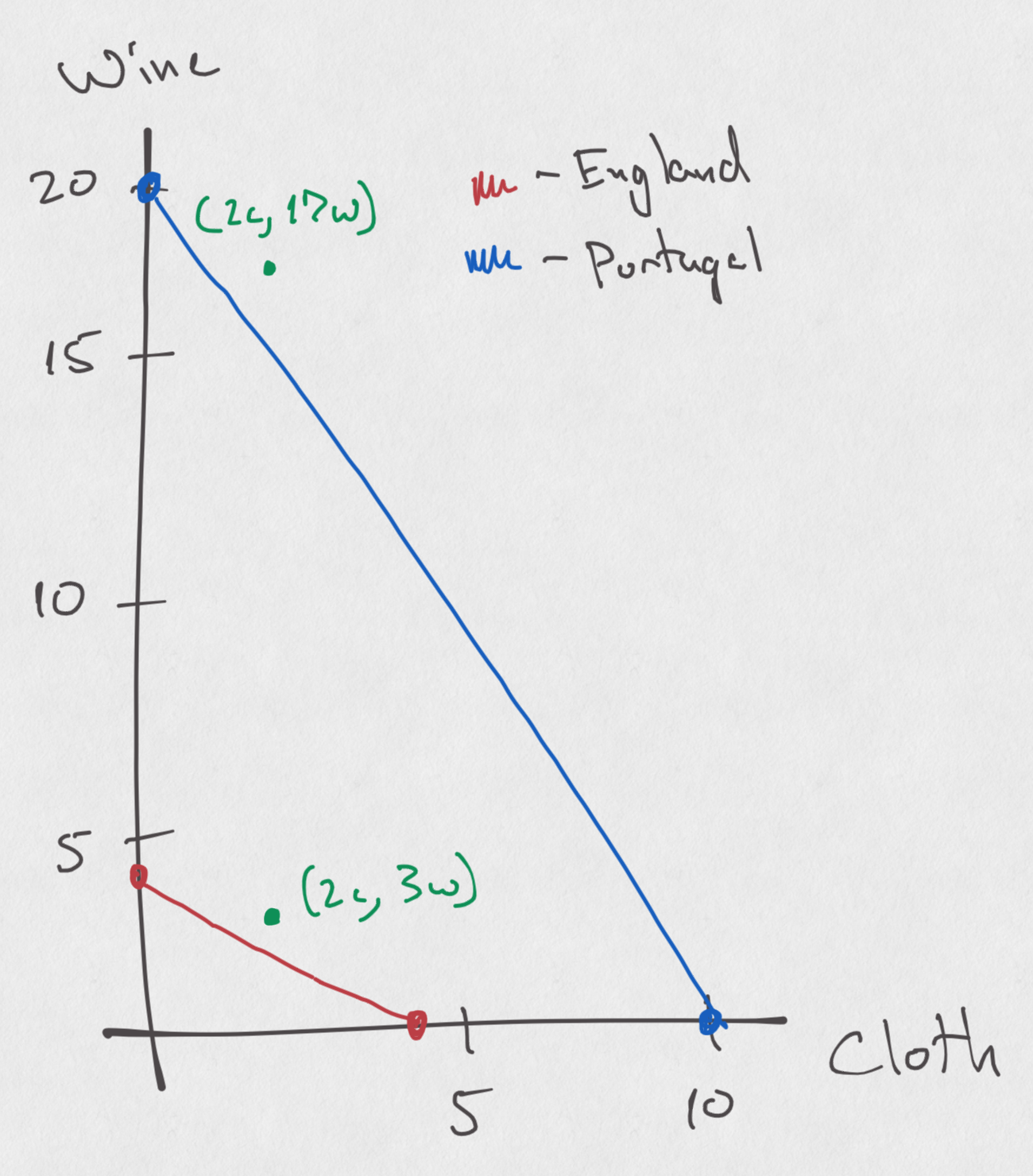

In that book, David Ricardo imagines a world of only two countries: England and Portugal, each of which produces some combination of only two goods: cloth and wine—the economist’s version of the old physics adage “assume a spherical cow in a vacuum”. Then, we draw some graphs to show just how much wine and cloth our imaginary England and Portugal can produce. For convenience, we’ll put them on the same axes and assume there’s a nice, linear tradeoff that is different for the two countries.

In this example, we have England in red, and able to produce (10 cloth, 0 wine), (0 cloth, 5 wine), or any combination on the line connecting those two points.

Likewise, we have Portugal in blue, and able to produce (5 cloth, 0 wine), (0 cloth, 10 wine), or any combination on the line connecting those two points.

Side note: the lines we’ve drawn are called production possibility frontiers, because they represent a set of all the points of maximum production that each contry can achieve on its own.

Why maximum? Because it stands to reason that if say, England, can produdce (10 cloth, 0 wine), they could also give half the country the day off and instead produce (5 cloth, 0 wine), thus achieving a point “inside the frontier” (aka - closer to the origin). We don’t consider those points any further however, because this whole analysis is about maximizing production, and intentionally producing less than you are capable of is a terrible way to do that.

Hereforth, we will often use the acronym PPF in place of the full term “production possibility frontier” because I don’t want to keep typing it out.

Now we imagine that both Engalnd and Potugal want some cloth and some wine. After all, without cloth, they’ll freeze in the winter for lack of coats, and without wine, all of their sommeliers would revolt. So how much cloth and wine can our England and Portugal get their hands on?

First, the situation without trade.

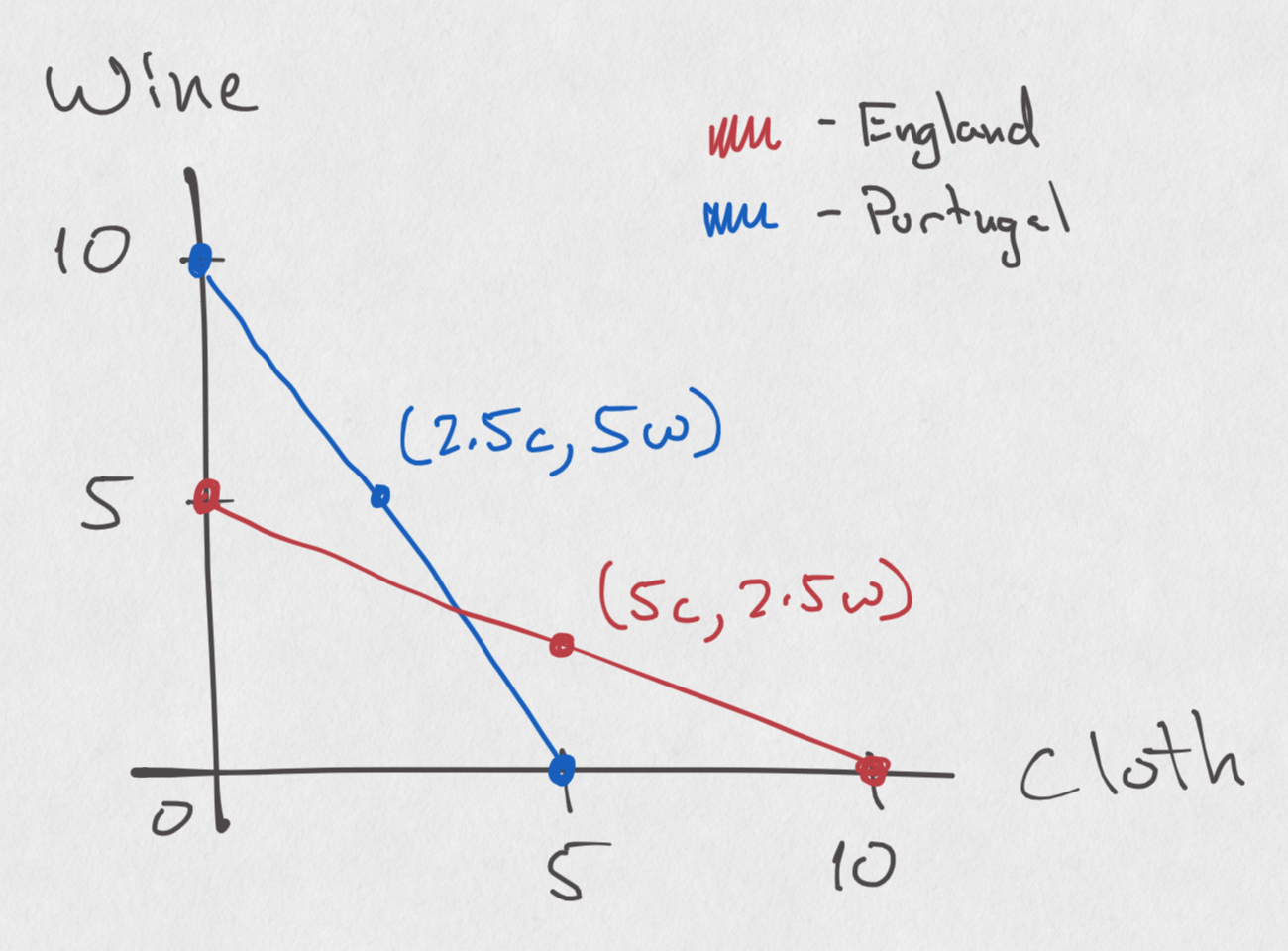

If our England is willing to devote itself 50:50 to the production of both cloth and wine, they will end up with (5 cloth, 2.5 wine).

Likewise, our Portugal will end up with (2.5 cloth, 5 wine).

I’ve marked these points on the graph below.

Can we do better?

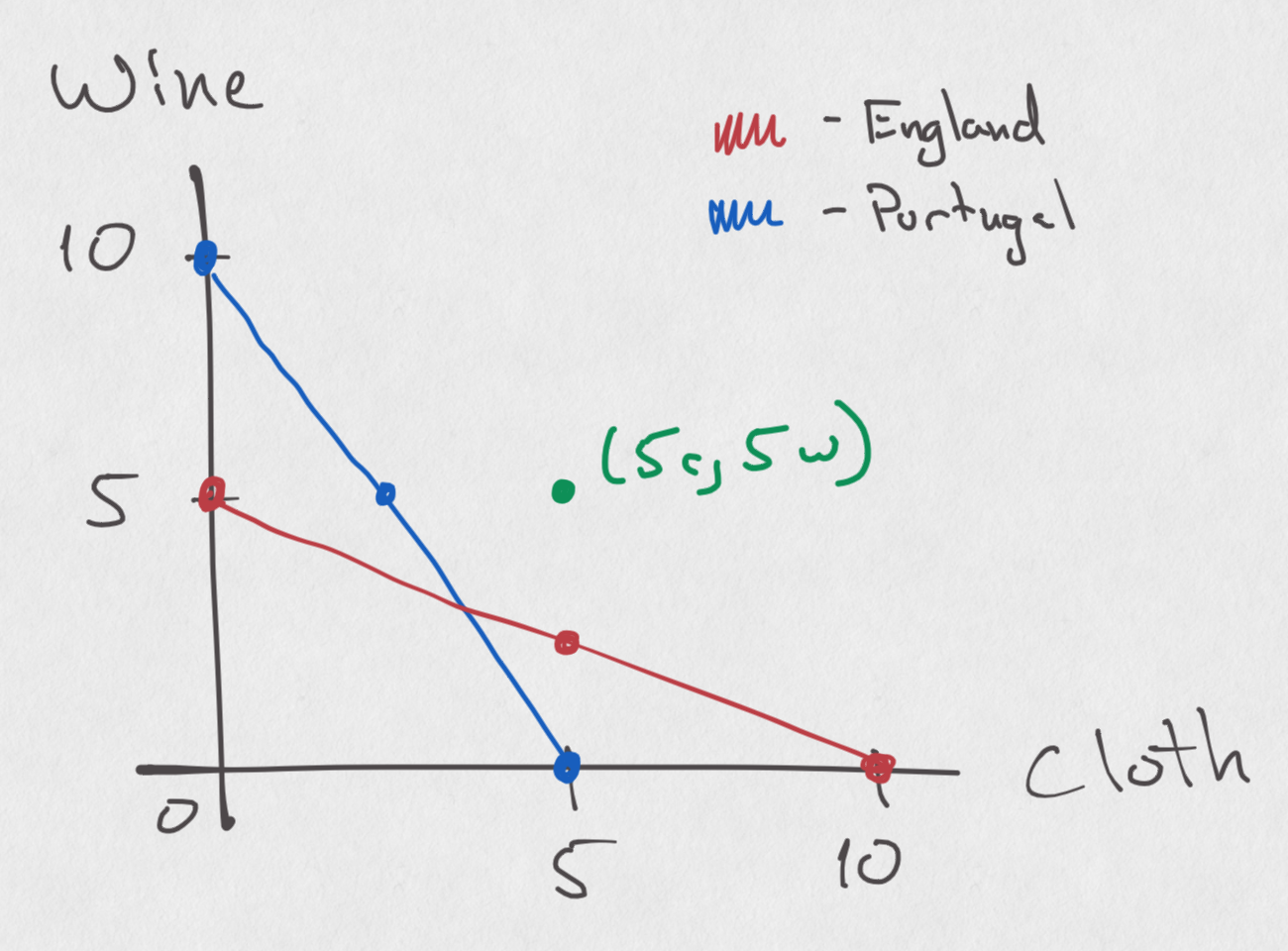

Yes! As an example, imagine if England only makes cloth, and thus starts with (10 cloth, 0 wine). Likewise, have Portugal focus solely on wine, starting off with (0 cloth, 10 wine).

Now, suppose the leaders of the two countries, seeking to satisfy both their cold peasants and their thirsty sommeliers alike, get together and agree to trade half of England’s cloth in exchange for half of Portugal’s wine.

Now England ends up with (5 cloth, 5 wine), and Portugal also has (5 cloth, 5 wine).

Notice how when each country focused on what it was good at making, and traded to get what it wasn’t good at making, both countries ended up better off (i.e. - with more total stuff) than either could have been alone.

But what if one country is better at everything than the other?

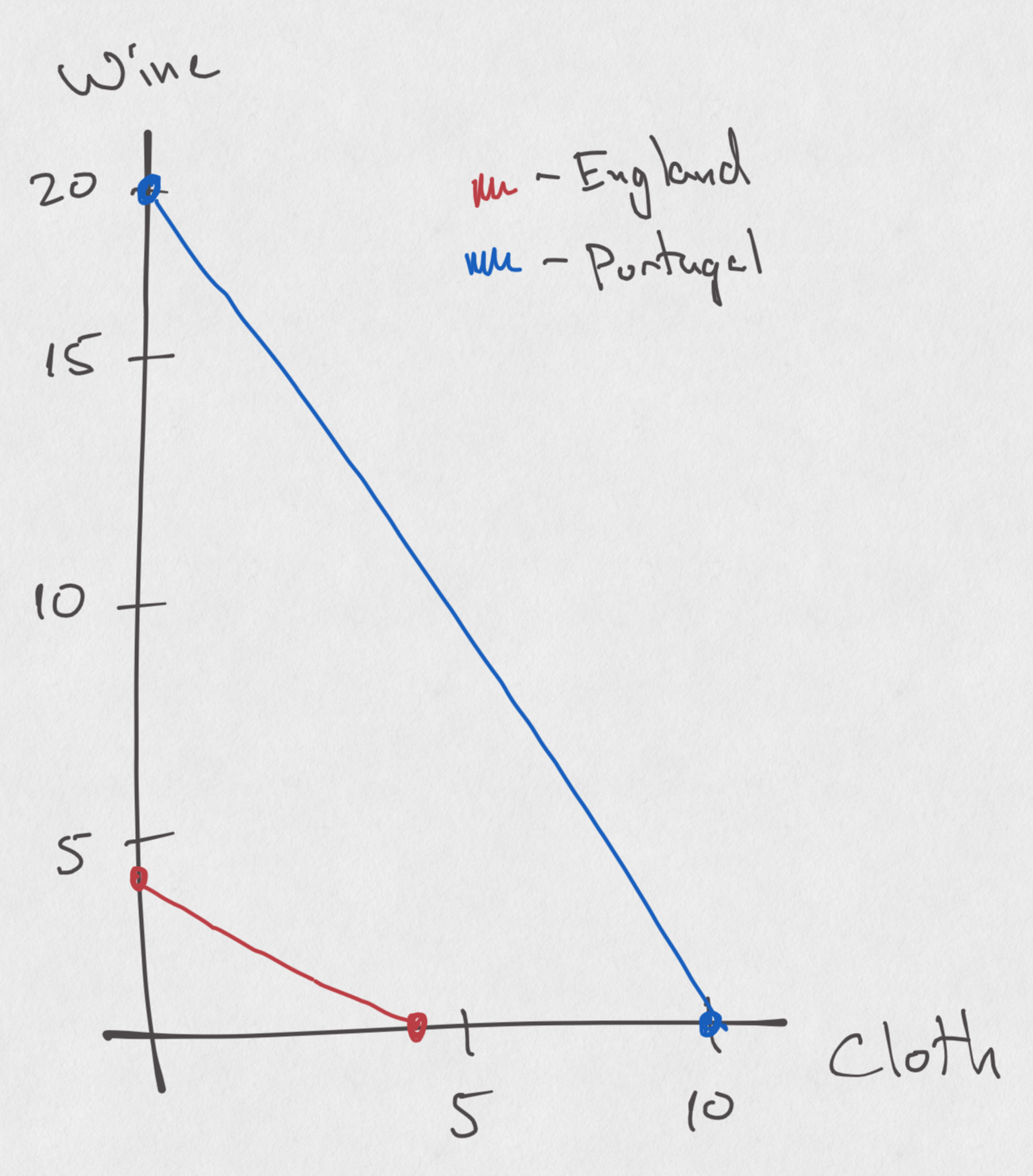

Not so fast! Let’s look carefully at what happens if we change our example in a way so that one country, say Portugal, can simply produce more of everything than our England.

Here, our Portugal is a beast, able to produce (10 cloth, 0 wine) or (0 cloth, 20 wine), or anywhere in between.

Likewise, our England has become shrimpy, and can only manage a production of (4 cloth, 0 wine), (0 cloth, 4 wine), or anywhere in between those two.

On their own, if each country splits its focus 50:50, we end up with England at (2 cloth, 2 wine) and Portugal at (5 cloth, 10 wine).

And now, with focus and trade!

England focuses on cloth, starting out with (4 cloth, 0 wine).

Portugal focuses on wine, starting out with (0 cloth, 20 wine).

Again, their leaders meet and discuss a trade. This time it’s a little more complicated, so let’s look at one country’s perspective at a time.

England knows that on their own, they can just adjust their focus and essentially “trade” 1 unit of cloth for 1 unit of wine (because the points (4, 0), (3, 1), (2, 2), etc are all on their PPF). Therefore, if they can trade 1 unit of cloth to Portugal for more than 1 unit of wine, England will be getting a great deal, will profit handsomely off of the trade, and will end up with more total cloth and wine than it could make on its own.

Portugal, likewise, finds that on their own, they could just adjust their focus and essentially “trade” 1 unit of cloth for 2 units of wine. Therefore, as long as they can get 1 unit of cloth from England for less than 2 units of wine, the trade will be profitable for Portugal, leaving them also with more total cloth and wine than they could make on their own.

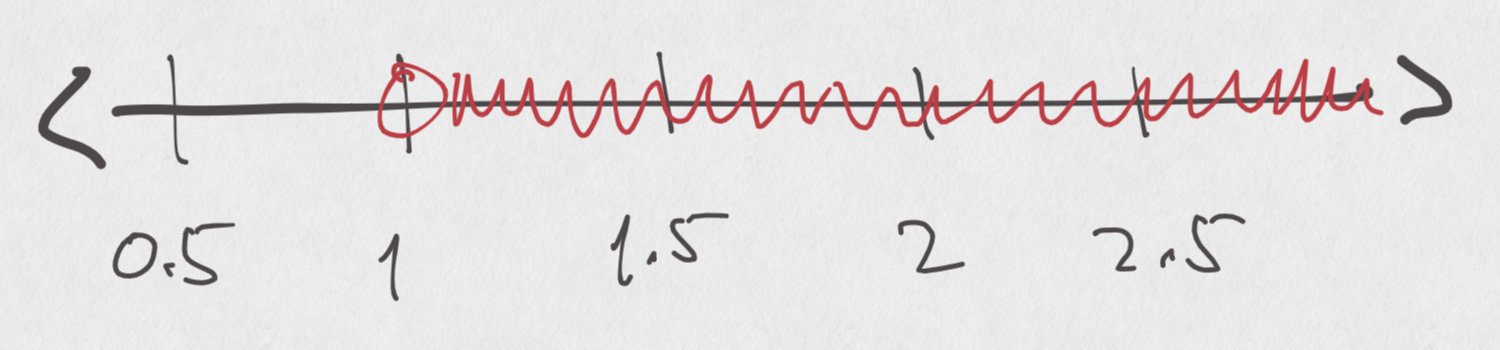

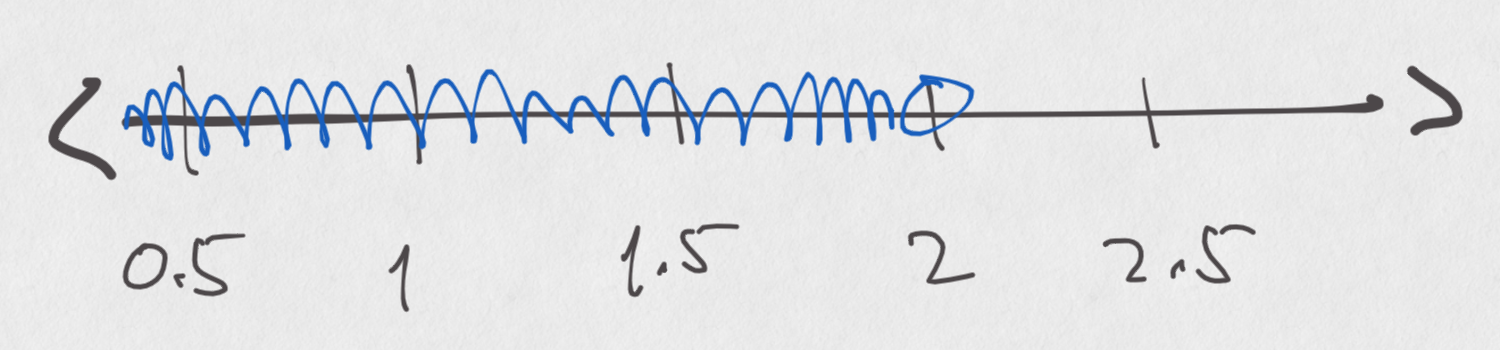

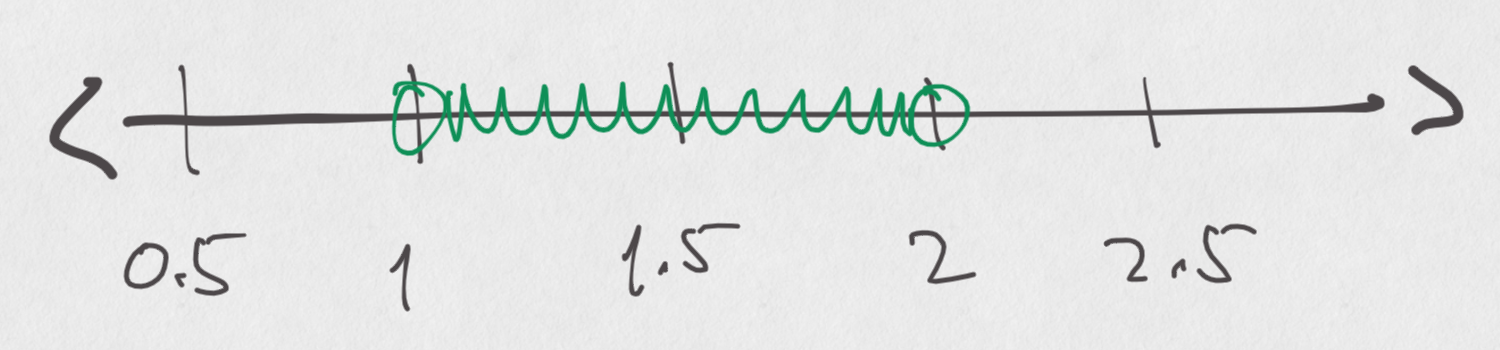

On a number line:

How many units of wine should we trade for one unit of cloth?

prices that make England happy

prices that make England happy

prices that make Portugal happy

prices that make Portugal happy

prices that make both happy

prices that make both happy

Since there’s plenty of overlap that makes both countries happy, they can pick a trading price for cloth:wine, and both end up better off.

To make it really concrete, imagine that they settle on a trading price right in the middle of their range—1 unit of cloth for 1.5 units of wine—and that they agree to trade a total of 2 units of cloth for 3 units of wine between them.

In this case, our England ends up with (2 cloth, 3 wine), while our Portugal ends up with (2 cloth, 17 wine), and again, they both have more total cloth and wine than they could have made on their own.

“Absolute” vs “Comparative” advantage:

Absolute advantage refers to an entity being able to produce more of something if that was its sole focus. In our first example, England had an absolute advantage in the production of cloth while Portugal had an absolute advantage in the production of wine. maybe it’s no surprise then, that they could both gain from trade.

Our second example was different, though. There, Portugal had an absolute advantage over England for the production of both cloth and wine! Yet both countries were still better off by focusing and trading. How can this be?

Simply because the abilty to gain from trade doesn’t depend at all on absolute advantages, but just on the two entities having different comparative advantages. These comparative advantages come from having different opportunity costs. In our second example, we said that England would be happy to trade 1 unit of cloth for more than 1 unit of wine, because that was the rate that they could get by essentially “trading with themselves” and just adjusting their focus. More carefully, we would say that “the opportunity cost for england to produce 1 unit of cloth is 1 unit of wine”. Opportunity cost is what you have to give up in order to achieve something.

Likewise in our second example, Portugal’s opportunity cost for producing 1 unit of cloth is 2 units of wine. Note that we’re essentially just comparing the slopes of the two PPFs: as long as they’re different, the two entities will have different comparative advantages.

In particular, the two slopes for any two entitites to produce any two goods are almost always different, even if only by a small amount. This is simply because everything about the two entities has to be basically exactly the same for the slopes of their PPFs to be the same, and if anything is different—and there are many more ways for things to be different than for them to be the same!—then the slopes will be different. Different slopes ⇒ different comparative advantages ⇒ both entities will be better off if they focus on one thing and trade for the other.

Ok, that works for countries, but for people? And what’s this about trading with yourself?

It’s true that we used contries (England and Portugal), and the production of physical goods (cloth and wine), in our example, but there’s no reason we have to limit ourselves to that formulation. We could have just as easily discussed people (say, an accountant and a baker) and the production of services (tax forms and cooked lunches). You see this exact example whenever you go out for lunch, thereby trading something you have a strong comparative advantage in (whatever your job function is) for something that you don’t (the lunch you eat) with another entity (the restaurant) that has a comparative advantage over you in that second good (producing lunch).

In the real world, you happen to conduct these trades with the aid of money, but while the details around that are a subject for another time, the basic idea is exactly the same. You focus on producing what you’re good at (your day job) and acquire the things you’re not good at (lunch) by trading for them. Even making your own lunches doesn’t let you escape from this sort of trade, unless you also grow your own wheat, bake your own bread, culture your own cheese, etc. The reason you ever buy or sell anything is, at its core, to use the fact of different comparative advantages to exceed your own individual PPF.

Ohhkay… and trading with yourself?

Absolutely! Think of yourself during two different sets of life circumstances: the first you will be you at university (the “student-you”), and the second you will be you while raising an infant (the “parent-you”). For our production goods, we’ll consider travel experiences and skill at drawing.

First we ask whether either “you” has a comparative advantage in producing either good. The answer is yes!

Student-you happens to have a study abroad program at your university, where you can travel to a sister institution and live in another country for a semester, while substituting classes at that other university for ones required for your degree back home. For parent-you, on the other hand, traveling is a nightmare. You’re carting around an infant and all that infant’s things, you’ve got a job you have to take time off from, and even once you got to your destination, your itinerary would only consist of brief jaunts to tourist attractions in between naptimes and feeding.

But what about skill at drawing? Surely student-you could pick that up pretty easily, even by enrolling in a class for that at your university! Well, despite that absolute advantage (remember that term?), parent-you still has a comparative advantage in learning to draw. You see, parent-you has lots of down-time in terrible, horrible, 20-to-30-minute-long chunks at odd hours of the day whenever that infant is finally sleeping. Those chunks aren’t really long enough to accomplish any big task, so for most purposes, they’re wasted time. But for busting out some quick sketches alongside a book or class? Perfect (aka - nearly zero opportunity cost, since the time was likely to be wasted anyway).

And how does this let you trade with yourself?

Simple: by being clever. If student-you thinks through this calculation, then student-you can safely put off that nagging desire to learn how to draw and instead focus on landing a study abroad program, and exploring the heck out of another country while you’re at it, safe in the knowledge that when the time comes and you’re raising an infant, parent-you will have different comparative advantages, and can focus on learning to draw in your spare time.

At the end of everything, you’ll have excellent travel experiences and skill at drawing, and in greater quantites than you could have achieved by trying to go 50:50 on travel and drawing both while at university and while raising your infant.

Bam. Two entities (student-you and parent-you) focusing on producing the thing they have a comparative advantage in (travel experiences and drawing skill) in order to reach a final point beyond their indidivudal PPFs (trade).