Too much blue light at night sucks. That’s why people use software like f.lux on their computers and night modes on their phones, but that doesn’t solve the problem of ambient light. The problem is that for ambient light, you really want to be able to generate a gradual transition of the light color through different color temperatures, and while you can buy standard bulbs designed to mimic particular color temperatures, there are no good solutions for the variable case.

But we’ve got RGB LEDs, right? You’d think that somewhere in all those color combinations we could find something equivalent to any particular color temperature.

Here, the naive approach of googling fails you, as, at best, you land on websites that say things like “here are some example colors and matching RGB values that I eyeballed”, and at worst, “you can’t do it without trial and error, so good luck”.

Well, I’m here to tell you that there’s a better way, and hopefully we’ll learn something about sensory perception and colors along the way.

First, the tl;dr

I wrote a python module called Color_Match. You can find it here.

Once you’ve installed it, go look up the emission wavelengths of your RGB LEDs on their datasheet. If you can’t find them, you can try starting with something like 623nm, 528nm, and 470nm (some example wavelength values from some RGB LEDs I happen to have on hand right now), but your results may be a little off and require some tuning of the specific wavelengths.

Then, let’s say that you’re trying to generate the equivalent of 1900K light (roughly candle-light), you would use the following code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

import Color_Match as cm

# first, generate the expected sense vector for the color temperature in question

sv = cm.sense_vector(cm.planck_spectrum(1900))

# using the sample wavelength values from above, converted into units of meters,

# we can get the needed relative intensities of our RGB LEDs

relative_intensities = cm.rgb_composition(623e-9, 528e-9, 470e-9, sv)

# full_brightness_limit is whatever value corresponds to a maximum output on an

# individual RGB channel, typically this is 255

full_brightness_limit = 255

# desired_brightness is a value between 0.0 and 1.0 that represents how bright you

# want your LEDs to be running; e.g., use 0.5 for 50% brightness

desired_brightness = 0.5

# since the values stored in relative_intensities are... relative intensities, we

# need to scale them to produce the correct absolute settings for your RGB channels

absolute_rgb_levels = (desired_brightness * full_brightness_limit) * relative_intensities

Now let’s talk details

What is light, really?

“Light” is the common term for electromagnetic waves (think of these like sine or cosine waves from math, or even like sound waves from a musical instrument), a self-propagating form of one of the four fundamental forces of nature. For our purposes, these waves have two properties that we care about: wavelength and intensity.

Wavelength simply refers to the physical distance in between one peak of the wave, and the next. When we talk about “light”, we’re usually implicitly referring to “human visible light”, which has a wavelength range of roughly 380nm to 740nm. “nm” refers to “nanometers”, or 10-9 meters. That means that the wavelength of visible light is tiny. Really tiny. Like, way smaller than even the tiniest bug you’ve ever seen, no matter if you were looking at it through a microscope or not.

Intensity is a measure of how much “oompf¹” the light has at any given wavelength. In reality, this usually has units related to energy, but for our purposes, you can just think of it as the brightness of the light.

The last important thing to know is that we usually think of the intensity and wavelength of light as being related. In particular, since each different wavelength of light can have a different intensity, we think of intensity as a function of wavelength. Or, mathematically,

This idea (that each wavelength can have its own, unique intensity associated with it) is really important, and forms the basis of the idea of a “spectrum”. In fact, a spectrum is just the particular function intensity(wavelength) associated with a particular light source.

Many different light sources have equally different spectra. Here are a few examples:

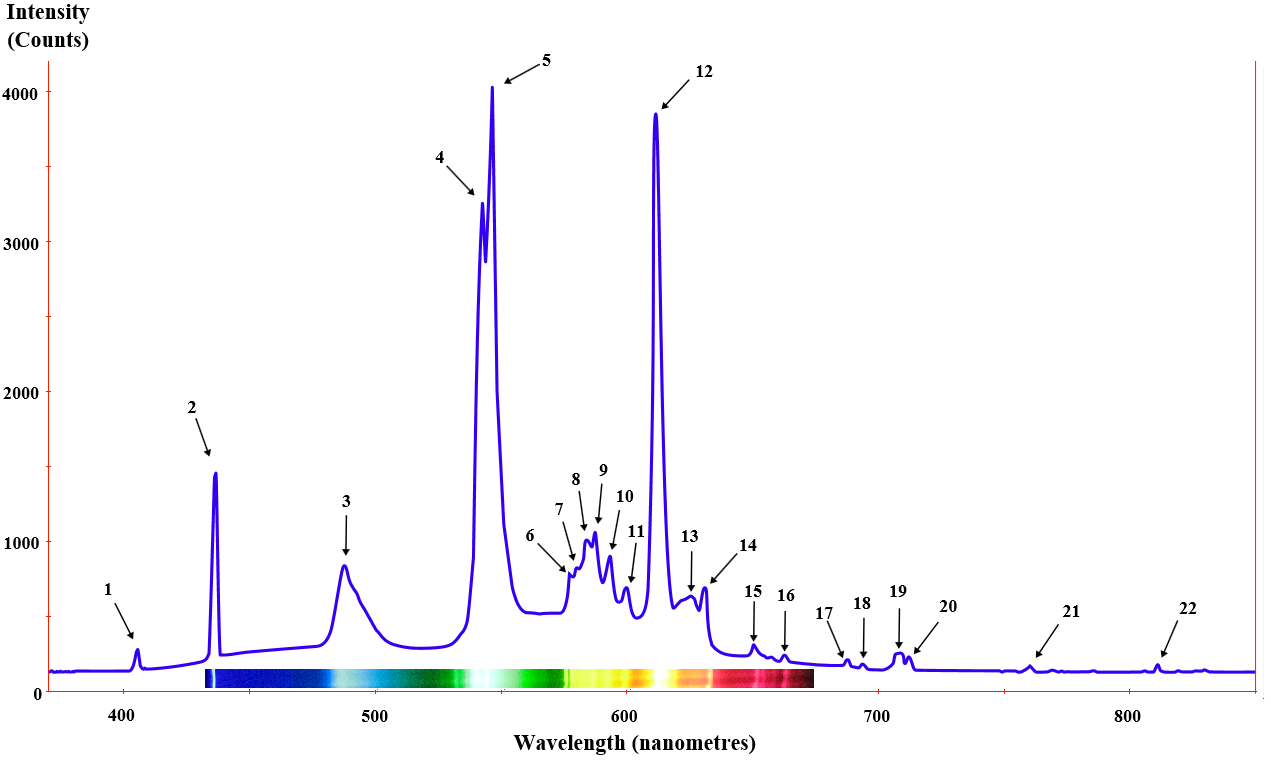

Fluorescent light spectrum from the wikipedia article on fluorescent lamps

Fluorescent light spectrum from the wikipedia article on fluorescent lamps

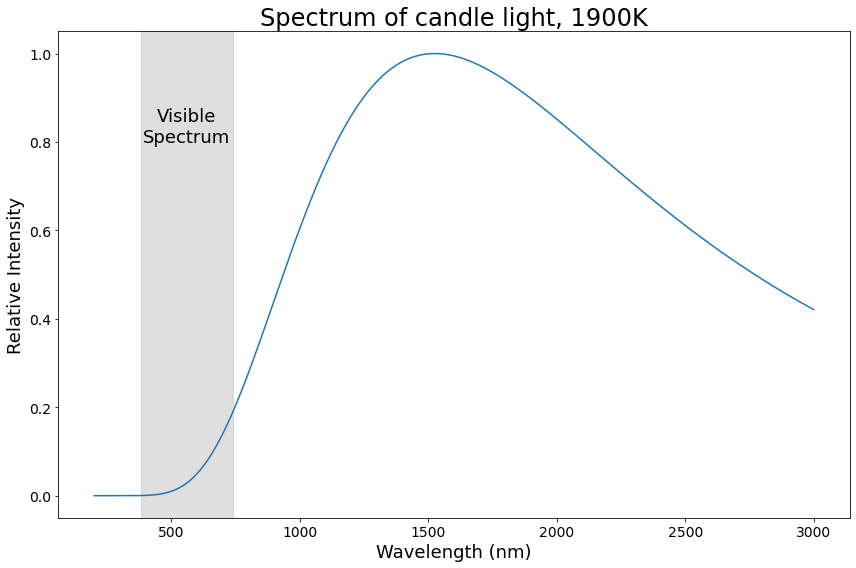

Candle light spectrum, 1900K

Candle light spectrum, 1900K

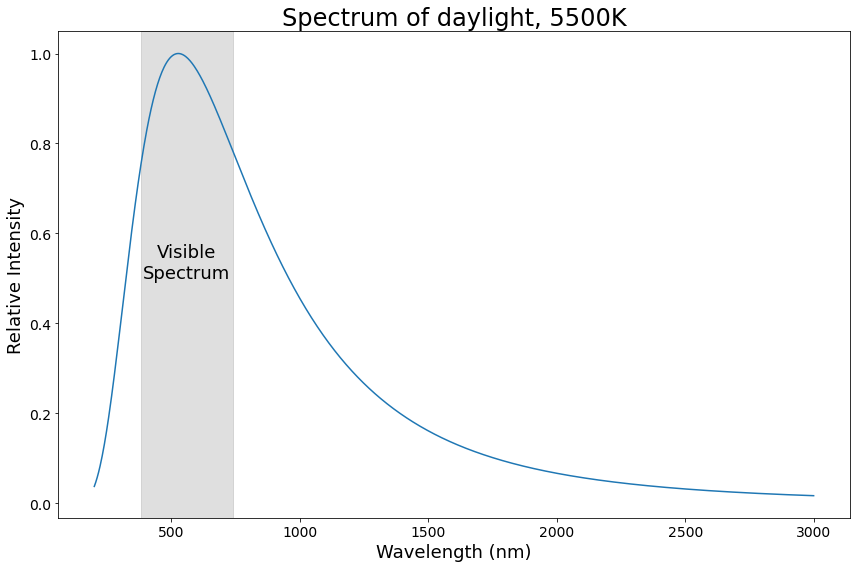

Daylight spectrum, 5500K

Daylight spectrum, 5500K

Did you notice how the spectra for candle light and daylight look a lot like each other? Let’s talk a bit more about that.

Within the wide world of all the different kinds of spectra, there’s one particular kind that we’re going to focus on: black body spectra. This refers to the spectra produced by a perfect absorber/emitter of electromagnetic waves (thus the ‘black’ part of the name, because a perfect black object would be both a perfect absorber and emitter, in much the same way as a black t-shirt on a sunny day absorbs lots of sunlight and heats you up quickly).

The nice thing about black body spectra is that their intensity(wavelength) function depends only on the temperature of the black body itself!

Now, that probably sounded complicated, but here’s the simple way to think about it: when you heat something up, it glows. You’ve seen this with pieces of charcoal, with electric stove coils, and even with video of molten metal and glass. If you heat it up to different temperatures, it glows different colors (lower temperatures are more red, higher temperatures are more yellow, etc). And for this kind of glowing, it doesn’t really matter what shape the object is, or even what it’s made of; the only thing you need to know to figure out what spectrum it’ll have is how hot it is.

This is also why the spectra for candle light and daylight above look so similar: they’re both black body spectra! The candle has a temperature of ~1900K, and the noon sun is ~5500K, but otherwise, their spectra come from the same physical phenomenon.

For convenience, when we talk about 1900K (or similar) light, we’re talking about light with a spectrum equivalent to that produced by a black body source with a temperature of 1900K. In this use, we say that “the color temperature of the light is 1900K”.

Then what are colors?

A true “color” then, from the perspective of physics, is just a combination of the spectra of whatever light sources are making up the light.

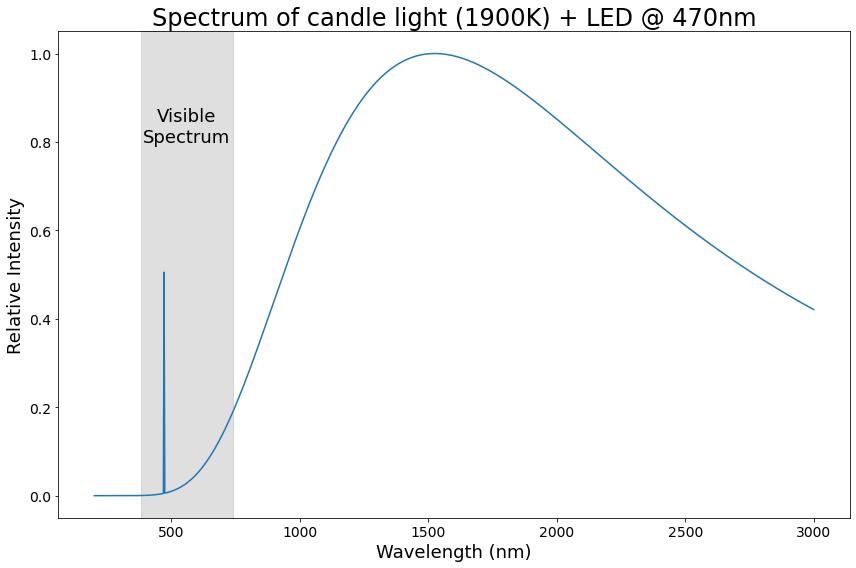

For example, if we have a bright LED shining in the same direction as a candle, we can find the true color of the resulting light by simply scaling their spectra to their relative intensities (remember, intensity == brightness), and adding them together!

Now, there’s one more important thing to know about true, physical colors: they involve a shit-ton² of information.

What do I mean by that? Well, since each wavelength within a spectrum has its own intensity, if we wanted to write down all of the information in a spectrum, we’d have to write down one intensity number for each wavelength number in the spectrum!

And how many different wavelengths are in a spectrum? Well, we might try counting, starting from 380nm on the low side. That might make us think that there were only 360 different wavelength numbers (380nm, 381nm, 382nm, …).

But what about in-between 380nm and 381nm? Are there any wavelength numbers in between those?

Sure! There’s 380.1nm, 380.2nm, 380.3nm, etc.

And… how about in between 380.0nm and 380.1nm?

Sure! There’s 380.01nm, 380.02nm, 380.03nm, etc.

At this point, you might be seeing a pattern. No matter how far we have “zoomed in”, we can always “zoom in” a little further and find more wavelength numbers. In fact, this means that there are an infinite number of wavelength numbers available in visible light spectra!³ That means that we’d need to write down an infinite number of intensity numbers to write down all the information in a spectrum!

In physics terms, then, a spectrum is an infinite-dimensional vector (one dimension for each wavelength!). That means that it contains an infinite amount of information! That’s a lot of information.

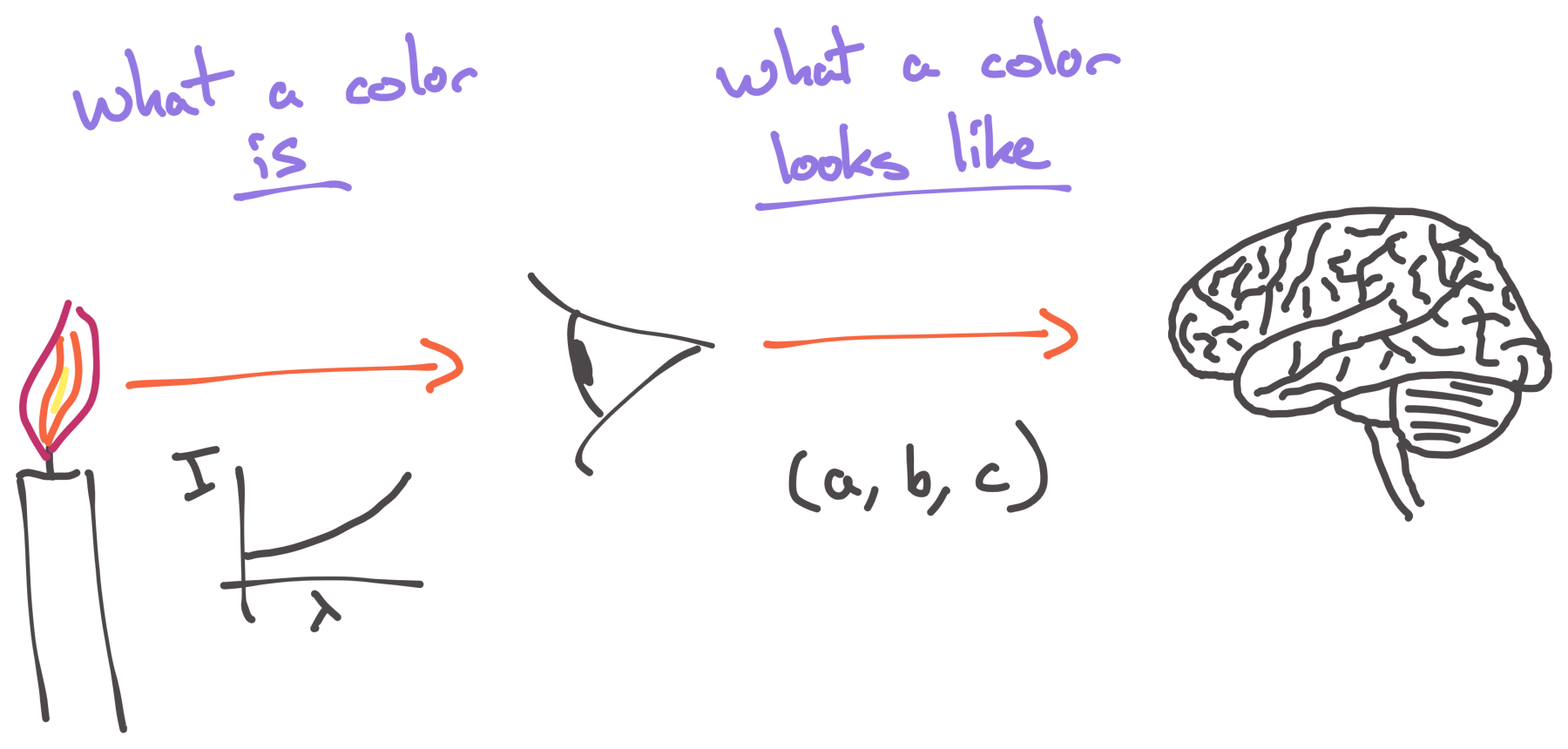

What do we mean when we talk about “what a color looks like”?

Unfortunately, our puny minds—ok, and the nature of physical reality itself…—are terrible at dealing with infinite amounts of anything, and so mother nature has played what amounts to a cruel trick on all of us and tied our ability to perceive color to certain molecules in the cone cells of our eyes.

The way this works is that when light of a given spectrum enters your eyes, it interacts simultaneously with all of these different molecules, and each kind of molecule acts like a certain kind of filter, responding selectively to different wavelengths within the spectrum. The greater the intensity of the spectrum at those wavelengths, the greater the signal produced by that particular kind of molecule in your eye. Your optic nerve, then, takes the signals from these molecules, and shuffles them off into your brain.

This whole process is a form of lossy compression. An infinite-dimensional spectrum comes in the front of your eyes, it gets sampled by a finite number of different kinds of molecules, and each kind of molecule essentially produces a number and sends that onward to your brain.

Since we’re going from an infinite-dimensional spectrum to a finite-dimensional set of filters, we’re going to lose (read: “compress”) a lot of information along the way.

And… exactly how many different kinds of wavelength-sensitive molecules are there in the cone cells of your eyes?

Three.

Just… three.

Your eyes take an infinite-dimensional spectrum of light, with an infinite amount of information in it, and compress that down to just. three. numbers.

So when we talk about matching the appearance of a particular color temperature…?

Let’s put the pieces together.

Light of a particular color temperature enters your eyes. Its infinite-dimensional spectrum gets turned into three numbers by the cone cells of your eyes. Those three numbers are what your brain uses to tell different physical colors apart.

That means that you could imagine figuring out which three numbers your eyes will produce when they see, say, 1900K candlelight, and asking “how can I combine light spectra from non-candlelight sources so that when your eyes convert my new light into three numbers, they end up being the same three numbers as are produced by candlelight itself?”.

If you can find a way to combine different light sources to produce the same numbers going up to your brain as the 1900K candlelight would, then your brain won’t be able to tell your combo-color apart from the candlelight.

In other words, your combo-color will match the appearance of a particular color temperature (1900K in our example).

Ok. How do we do that?

Now it’s time for some math⁴.

Light of a particular color temperature enters your eyes. Its infinite-dimensional spectrum gets turned into three numbers by the cone cells of your eyes.

First, we need the spectrum. Since we’re talking about black-body light, we’ll use the black-body spectrum. Note that technically this is an intensity function of two variables (both wavelength and temperature), but once we pick the temperature we’re using, we can plug that in and we’ll be left with a simple function intensity(wavelength) that we expected. Also, we use the Greek symbol 𝜆 (“lambda”) for wavelength because it looks fancy and everybody else does it too.

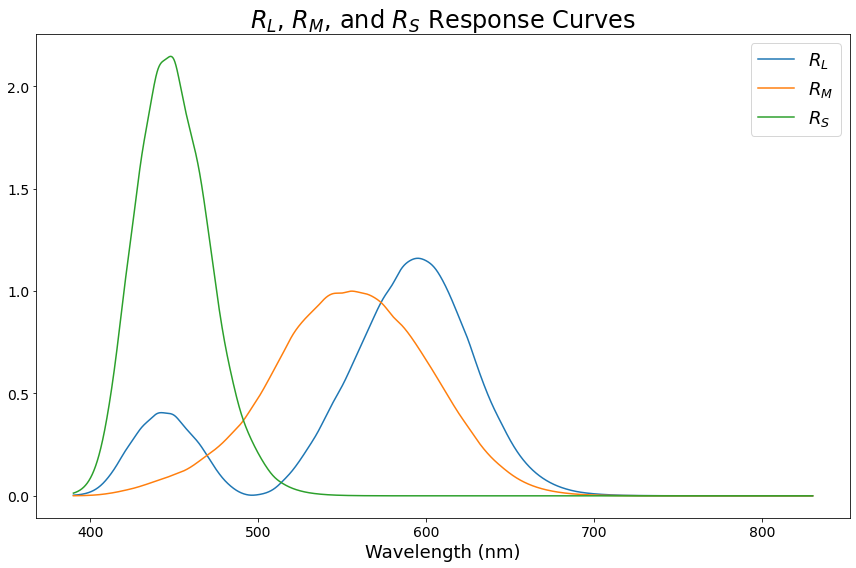

And once we have this spectrum, how do we determine those magic three numbers that your eye produces?

Well, your eye has three different kinds of color-recepting molecules in its cone cells. We call those the L(ong), M(edium), and S(hort) wavelength receptors respectively. So we’d love to take each one separately, and figure out how much it responds to each little portion of wavelength in the black-body spectrum.

In particular, if we have a response function for the L receptor (a function of wavelength),

Then the amount of response we get to a small slice (of width 𝛥𝜆) of the black body spectrum is approximiately

In order to know the total response of the L-receptor to the whole black-body spectrum, then, we have to take a bunch of these slices and add them all up. To be really accurate, we should do this while letting 𝛥𝜆 → 0, and drumroll, that means we’re taking an integral!

Let 𝜆₁ and 𝜆₂ respectively be the lower and upper bounds in wavelength of human vision, and you’ve got the L-receptor response to the black-body spectrum of a given temperature, T!

That’s it for the L-receptors, so now we have to do the same thing for the M- and S-receptors, and while we’re at it, we’ll cram the whole thing into a vector to make it easy to work with later on. We’ll call this resulting vector the “sense vector”.

And that’s it.

…almost.

I’ve hidden one thing inside of this explanation: just what is the response function, Rₓ, anyway?

In reality, it’s a complicated thing that includes both the actual molecular response of the receptors to the various light wavelengths, as well as the optical properties of all the other stuff “in the way”⁵ like the lens and vitreous humor. It’s not something you can easily derive theoretically, so we rely on measurements. Here’s what the Rₓ response curves look like:

It’s worth noting that the technical name for these curves are the “10-deg XYZ CMFs transformed from the CIE (2006) 2-deg LMS cone fundamentals”. If you’re interested in more detail, you can find the origin of the curves themselves here, and some more details about the derivation of them at this wikipedia page.⁶

If you can find a way to combine different light sources to produce the same numbers going up to your brain as the 1900K candlelight would, then your brain won’t be able to tell your combo-color apart from the candlelight

Above, we generated the sense vector from the black-body spectrum we were trying to match. Now we consider how to actually match it.

First, we need to know the spectra of our new light sources. For my particular purposes, I’m using RGB LEDs, which I’m modeling as having delta function spectra located at the emission wavelengths of the LEDs (from their datasheets).

In other words, for an LED of wavelength 𝜆ᵢ, the sense vector produced by it will be:

Or, after simplifying,

Where cᵢ is the intensity of our LEDᵢ. So, for three LEDs, we would add the three sense vectors together, and attempt to find the appropriate cᵢ values to match the sense vector from our black body spectra.

In other words, we’re trying to solve for the constants cᵢ below:

This looks ugly, but neverfear! We rearrange terms:

Now we make things even simpler-looking, by renaming our matrices so the next steps will be more clear.

Remember, by this point, both S and R should be simple things, full of just constants. So now, assuming that det(R) ≠ 0, we get our answer:

R and S are just full of constants, so we plug them in, do the math, and get out our values for the cᵢ’s, telling us what the relative intensities should be for our RGB LEDs to match the color we desire.

The last thing we might want to note is that the hue of the color is just determined by the ratios we use for our cᵢ’s. We can therefore control the overall brightness by simply scaling all three cᵢ values up or down by the same multiplier.

Some example values⁷:

Some other interesting, related things…

Having just three numbers sucks!

Remember how this whole discussion was based on the idea that true, physical colors in all their infinitely-detailed majesty undergo lossy compression in the back of your eyeball down to just three numbers?

Well, turns out that’s true for humans⁸. It isn’t, however, true for pigeons.

Pigeon portrait from Wikimedia Commons

Pigeon portrait from Wikimedia Commons

See those beady little eyes? They’re hiding pentachromaticity. That’s a fancy way of saying that when our little winged friend here looks at a color, her eyes turn each color into five numbers. And you know what? 5 > 3. BOOM. Pigeons.

But let’s be really clear about what this means: there are infinitely many instances of colors that you, as a perfectly functional human, can not tell apart, but which the average pigeon would have no trouble distinguishing.

You literally can not see the true majesty and beauty of the world of colors as well as a pigeon can. And you’re not even close. Eat that, Rembrandt.

So pigeons are really great, huh?

Nope. Being limited to five numbers sucks too.

Remember, we’re coming from an infinite-dimensional space of true, physical colors! Compressing down an infinite amount of information into just five numbers still throws out a mind-bogglingly large amount of information.

The real lesson? Pigeons are terrible at seeing colors. You’re just infinitely worse.

But at least we can kind of see the same range of colors, right?

Remember how we made the distinction early in this article about “human visible light” (that is, electromagnetic waves with a wavelength of between roughly 380nm - 740nm)? That’s because your eye simply doesn’t respond to electromagnetic waves outside that range. That is, you’re blind to them. Completely.

Most birds can see down to about 300nm (compared to the 380nm that you’re limited to).

Snakes have extra sensors that can “see” up to 30,000nm.

Hell, insects can even see the polarization direction of light!

And all that isn’t even to mention the fact that electromagnetic waves can have wavelengths outside of the still-tiny range visible to any animals at all (roughly 300nm - 30,000nm).

Just how big is the range of electromagnetic waves? The technical term is ginormous.

On the small side, x-rays range from rouguhly 1nm to 0.01nm in wavelength. Smaller still than those are gamma rays, around 0.001nm. And beyond that, we’ve observed VHEGRs⁹ with wavelengths down to about 0.00000000001nm. Can they go even smaller that that? Sure! We just haven’t observed any yet.

On the other end of the spectrum, infrared light covers the region of wavelengths between about 1,000nm and 100,000nm. After that, we have things like microwaves at 1,000,000nm to 1,000,000,000nm, followed by just bucketing everything larger than that into the category of “radio waves” which has some overlap with microwaves, and stretches from about 1,000,000nm all the way up to about 880,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000nm10.

And yes, I’m saying that radio waves have a color. Microwaves have a color. X-rays have a color. All of it is color, in the truest, physical sense. And you, human, you get none of it but the barest, tiniest glimpse through the smallest pinprick in an ultimate filter.

Humans are practically blind!

Yep! Now you’re getting it.

Better build more telescopes, observation satellites, night vision goggles, particle detectors, etc. They’re your only hope to actually dream of trying to attempt to come close to seeing the universe you’re surrounded by. Until then, just keep in mind that for every color you can distinguish, you’re missing out on an infinite universe of detail. Your existence is adrift in a sea of invisible ghosts and phantoms, such that even if we try very hard, and build very clever tools, we will only catch the barest glimpse of them.

-

This is the technical term for it. You can trust me. I’m a physicist.

-

Again, also the technical term for it.

-

This is a lie, but it’s close enough to the truth. If you want to understand the whole truth, go study Quantum Field Theory and the Planck Length.

-

My favorite part.

-

If you want to sound fancy, replace this with the phrase “in the optical path”.

-

I’m almost certain that large sections of this last paragraph (and, indeed, of the description of the pictured response curves as being directly related to the actual LMS receptor responses) are incorrect. But I’ll be damned if I’ve found good enough sources to fully understand what in the world is actually going on (How was the choice of construction of XYZ CMFs made? Why does one have a double-peak? How would you construct a new set for tetrachromats?). If you’re a proper color scientist, can you please point me at better resources to dig into this stuff? Until then, the confidence I have is that even if these response curves do not directly map to LMS receptor responses, they do fully span the space of LMS responses, so if we can match the sense vector produced by these curves, the resulting color should match in an actual person’s perception.

-

These are generated using RGB LED emission wavelengths taken from some datasheets I happen to have on hand (625nm, 530nm, 430nm). They may not appear exactly accurate on your screen if your screen has different emission spectra. If you use something like f.lux or redshift, then they definitely won’t appear right.

-

Seriously, tetrachromats, stop ruining all of my simple explanations with your edge-case existence.

-

VHEGR stands for Very-high-energy gamma ray. I promise I’m not making this up. And if you think this is uncreative naming, wait until you find out about the amazingly-named VLT and some of its proposed successors, the ELT, and OWL.

-

This is not a typo. The only upper limit on the wavelength of radio waves is the size of the universe.